I and We

Gallery 206 and 207

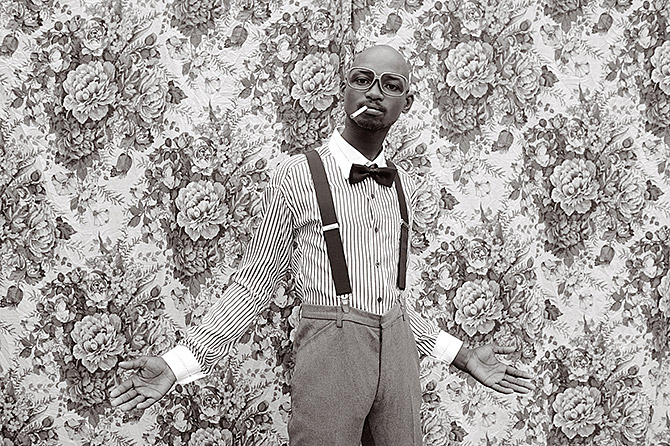

Social and cultural developments in Africa are not simply a matter of copying worldwide trends, as demonstrated by flourishing subcultures like Botswana’s heavy metal scene or the sapeurs in the Republic of Congo. Both groups avail themselves of western styling: either studded leather or dapper suits and panama hats. Yet the aesthetic codes are reinterpreted until a new, unique and distinctly African cultural form emerges. Fashion is also employed as a vehicle for exploring the boundaries between the sexes – from seduction to gender roles – and it supplies a means of expression for sexual minorities.

"In the world through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself."

Clam Magazine

CLAM is a unisex magazine that promotes ideas about fashion, architecture, music, design, the arts, leisure, travels, social entrepeneurs and African design. The founders regard the magazine as a forum for images: a place where images can be presented, shared and discussed.

Clam is published in Paris by Clam studio, which develops image concepts, graphic design and advertisements for clients. Over the past 11 years, it has been published twice a year, in Japan, the US, Europe, and Brazil. It’s translated into several different languages, and covers a wide range of interesting people.

The founders say: ‘The idea for the magazine was just to talk about what we really like. We do it because we like to do it. We don’t do trends. But I guess it’s still a fashion magazine, because it’s actually a magazine about creativity, presented visually. It’s also about social entrepreneurship, innovation, and a whole lot more, but it’s done from a very humane point of view’.

Okhai Ojeikere: Hairstyles

Nigerian photographer J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere worked on his Hairstyles series for several decades, turning Nigerian women’s heads into artworks.

For over 40 years, Ojeikere documented the diversity of Nigerian hairdressing in a total of nearly 1,000 photographs, creating a historical archive that illustrates the country’s aesthetic development and the great cultural diversity in its hairdressing industry. His photographs were taken on the street, in offices and at parties. The images follow a strongly systematic approach: the black and white photographs are always taken from above, sometimes in profile. The images’ contrast highlights both the high level of abstraction and the sculptural aspect of the hairstyle. Ojeikere liked to watch the creators of these artworks – the hairdressers – while they worked, and used his photographs to transform their professional accomplishments into sculpture.

Mário Macilau: Moments of Transition

With his Moments of Transition series, photographer Mário Macilau aims to capture the search for identity of contemporary young Mozambicans.

The photographs are all taken on Sundays, when the urban youth have the time and the opportunity to dress how they like and act as they wish, spending a relaxed day together. Their clothing style is an ever-changing mixture of urban fashion and traditional clothing, in a never-ending competition where those who want to make an impression needing to prove their stylishness anew every time. With their choice of clothing and attitude, the youngsters of Maputo do not simply want to impress others; their style enables them to ensure a place in the group, creating an individual identity and to conveying it to the world. This youth movement is greatly influenced by western fashion and lifestyle. Students that return to Mozambique from Europe bring new influences from the fashion industry, and the flourishing second-hand market ensures an increasing demand for European clothing. However, Macilau’s visual language also pays tribute to the heyday of African studio photography in the mid-20th century, creating a connection to a generation that, just like the current African youth, laid claim to a great future and consequently adopted a style that matched these expectations: the generation of the 1960s and 1970s, who celebrated their liberation from colonialism.

MISWudé: Waxology

Waxology is the result of a cooperation between the jewellery and fashion brand MISWudé and photographer Fabrice Monteiro.

The body jewellery is made with the aid of wax-dyed cotton fabric cut into strips, processed using various different techniques and then brought into shape. Both material and form refer to traditional African handicrafts; the aesthetics, however, are also reminiscent of 18th century anatomical studies. At the same time, the body jewellery items play with the same kind of subtle erotica that is typical of sexy underwear in West Africa – in that it enhances, while concealing the body. What is key for understanding the work, however, is the role of wax, the cloth that also gives the work its name. Crucial for West Africa’s aesthetic industry, this fabric stands here for Africa’s lacking sovereignty. It is a product of colonial expansion that has never been manufactured in Africa and today, it is linked with Africa only at the level of consumption and processing. The creative and constructive re-interpretation of the cloth in Waxology – its cutting and re-joining – liberates it from its colonial context, thus symbolizing nothing less than the re-invention of an African aesthetic identity.

Malick Sidibé: Nuit de Noël (Happy Club)

This picture was taken on Christmas 1963 in Bamako, probably very late at night, given the empty bottles on the floor that can be discerned in the background. In the centre, an African couple is dancing. She is barefoot and wearing her best dress, he is wearing loafers and a smart white suit. Their heads close together, they smile and dance to the rhythm of western music, probably rock’n roll or the twist.

This striking photo is full of intimacy, verve and joie de vivre. It was taken by photographer Malick Sidibé on one of his tours of the booming nightlife in Mali’s capital at the beginning of the 1960s. Sidibé is one of the few who captured the blossoming lifestyle of a new, self-confident generation of Africans liberated from colonialism, with a passion for western fashion and exuberant parties: lanky men in perfectly tailored bell-bottoms and platform shoes are enjoying the company of pretty women in glittering mini-skirts and fashionable sandals. Sidibé, who was part of this new youth culture himself, took photos of several parties every night, developing them at dawn in his studio and selling them the next day – like hot cakes. “Music freed us,” he has said. “All of a sudden, young men were allowed to approach young women and hold them in their arms. This was not allowed before. Everyone wanted to have a photo taken of themselves dancing so closely. And then they wanted to see the pictures immediately!”

Omar Victor Diop: The Studio of Vanities

With his project The Studio of Vanities, Omar Victor Diop draws the viewer’s attention to the blossoming art and culture scene in Dakar, portraying the hippest artists, designers, fashion designers, and musicians of his generation.

The result is a collection of individual portraits, striking and captivating in their charm. Diop carefully chooses backgrounds and patterns to strengthen the subject’s personality and cultural references. Therefore, the colour of kenté fabric flawlessly matches the outfit of casually posing fashion designer, Selly Raby Kane. The clothes of artist Mame-Diarra Niang and model Aminata Faye fuse with an African background pattern. Using this particular approach, Diop becomes part of a tradition of African studio photography epitomized by the likes of Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta. He honours their pioneering work in his own creations, making use of contemporary techniques. Instead of merely creating striking images of an attractive young generation, Diop defines the images during the portraiture process, ensuring that decisions regarding pose, background and props are taken together with the subject. This makes it possible for Diop to come closer to the essence of the portrayed individual, and therefore do justice to the multiplicity and energy of Dakar’s contemporary cultural scene.

Wangechi Mutu:

The End of eating Everything

This animated short film is called The End of eating Everything, and is a collaboration between Kenyan-born visual artist Wangechi Mutu and creative badass Santigold.

In it, a Medusa-like female, played by the North American singer Santigold, hovers above a post-apocalyptic landscape. She comes across a swarm of birds and greedily begins to eat them. Her throbbing, monstrous body gradually becomes visible, covered with lesions. She sprouts human limbs, parts of machines, and her pores spew out poisonous smoke. She finally implodes, giving birth to numerous female heads. This monster symbolizes planet Earth and the unending consumption of modern society.

The film combines some of Wangechi Mutu’s most important creative inventions to date. These include her 2005 Tumor Series, in which she used cancer as a metaphor for our current state of existence. Likewise, in The End of Eating Everything the planet-like creature is lost in a polluted atmosphere, and led by hunger towards its own destruction.